Beyond Gunpla and Bishounens

A.D. 1999- While most girls of my age would declare their love for Tamahome, Hotohori, or any of Miaka’s Suzaku no Senshi, my friends and I spent our afternoons geeking about the pilots and mobile suits of Gundam Wing.

For some purist fans of the series, Gundam Wing was an insult to the Gunpla franchise and was looked down for having bishounen looking characters. They o ften accuse the series as a mecha series created for girls (Read: Frozen Teardrop). Well, it’s a crime as an anime/manga fan to not have appreciation for good-looking fictional characters, especially if they pilot awesome looking mobile suits.

ften accuse the series as a mecha series created for girls (Read: Frozen Teardrop). Well, it’s a crime as an anime/manga fan to not have appreciation for good-looking fictional characters, especially if they pilot awesome looking mobile suits.

Back in the age of dial-up connection and prepaid internet cards, fangirling for a franchise whose demographics are mainly males and toy collectors was difficult. I relied on anime websites, and Tokyo Pop serialization of the manga. My interest for plot became my introduction to Japanese studies, as well as to International Relations. Beyond the gunpla kits, doujinshis, and other fandoms, the Wing series owns a rather realistic plot. Of course, the fictional roots of the Gundam series was born out of Japan’s traumatic cultural and political history.

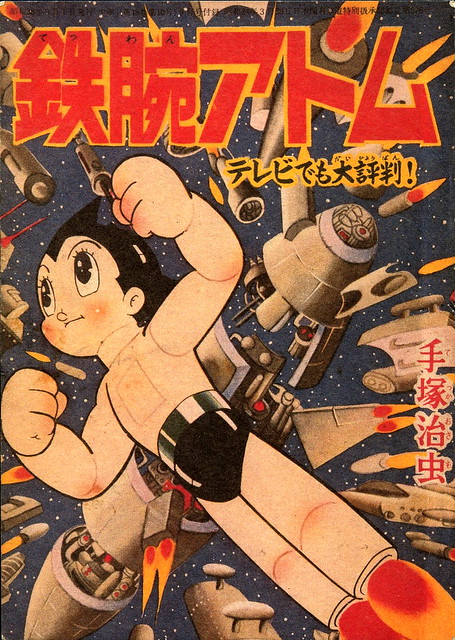

The cultural history of the mecha/robot culture in the 1960s was an indicator of the improving economy and industrial technology of post-WWII Japan, which prospered during the event of technological revolution: the television. From here, sub-genres of the mecha/robot anime flourished. Most mecha/robot series (like Astroboy, Tetsujin-28, and early tokusatsu series) promised a bright future with more advanced technology and space age gadgets and vehicles. However, the birth of Gundam in 1979 introduced a different face of the Mecha/Robot genre. Mobile Suit Gundam was “introduced as a sort of paradox: a war show about giant war machines that was in fact anti-war at heart.” (Hikawa, 5) The series echoed fragments of Japan’s social, cultural, and political memories of WWII and the rebuilding of a nation and its identity after the war.

Each series is set in its own fictional universe (Universal Century, Future Century, After Colony, Common Era, etc.), dealing with war narratives between fictional nations (colonies), and characters undergoing their own bildungsroman. The different series and timelines of Gundam does explore different social science issues.

For now, I’d like to concentrate on the turmoil of the After Colony (A.C.) timeline. The A.C. timeline was born out of failed international relations, death of a leader, and twisted obsession for justice and freedom in a form of defense treaties.

The familiarity of the fictional events does not only reflect pieces of history, but a sneak of a possible future. The idea of space colonization began way back in the 1980s. A former member of United States Department of State mentioned in Foreign Affairs journal that colonies will protect humans in case of a global nuclear warfare. This very same idea is used in Gundam Wing.

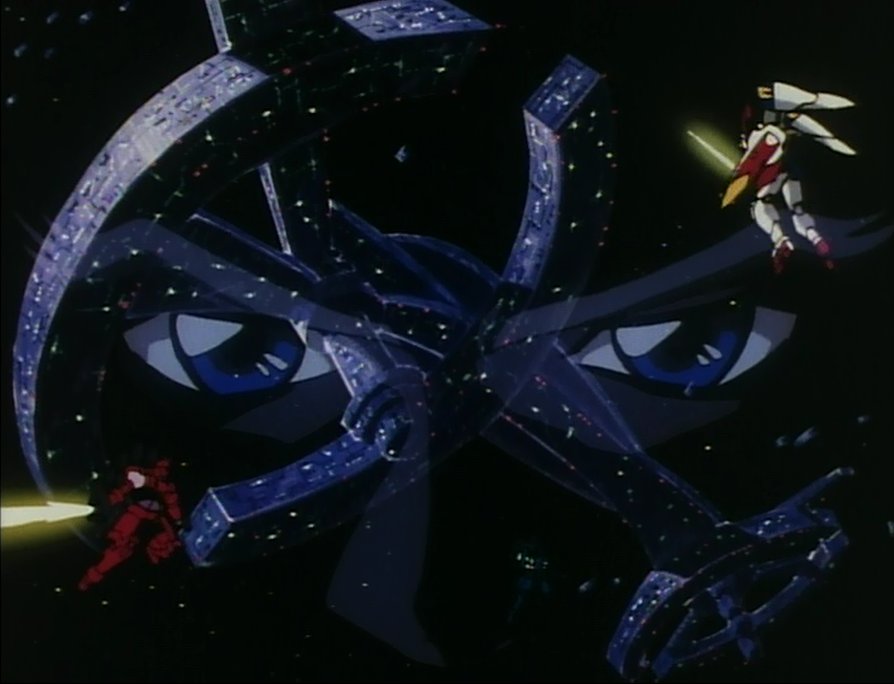

The creation of the Lagrange colonies by nations served as migrant spaces for fleeing nations due to rising international disputes, These space colonies are not just scientific, but political and economic as well. Each colony in the Lagrange point is composed of different nations, with economic similarities to the ones they have on Earth. L1 colony is an island-type for multiple colonies (nations), L2 and L3 were undescribed, but composed by multiple nations, L4 cluster is similar to the Middle-East and is occupied by oil magnates, while L5 owned by a clan exiled from China. The identity composition of the colonies somehow represents the present economic standing of different nation-states. However, economic stability doesn’t equate to political standing. The supposed to be governing body between nations and colonies, in the form of United Earth Sphere Alliance (UESA) became the very fuel of the continuous dispute by the funding of Romefeller Foundatiion, a conglomerate that keeps a secret military known as OZ (Order of the Zodiac).

If we further dissect the fictional history of Gundam Wing, we’ll definitely find that the series is a political thriller, with complex characters masking different political agendas. (The character back stories can be further explored in the Frozen Teardrop arc.)

The romanticism for war, obsession for power, and the thirst for change have always been catalysts for historical disputes. In the wise words of Mariemeia Kushrenada in Gundam Wing~Endless Waltz~, “History is much like an endless waltz; the three beats of war, peace, and revolution continue on forever.”

Relating it back to the traumas of war, as experienced by the Japan, Gundam is probably the Japan’s alternative war narrative- where in war atrocities were not part of their history and with the constant hope the peace will always reign and remain.

Sources:

___________“A Cultural History of Robot Anime”. Japanese Animation Guide: The History of Robot Anime. Commissioned by Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs Manga, Animation, Games, and Media Art Information Bureau, 1 Jan. 2013. Web. 17 Mar. 2015. <http://mediag.jp/project/project/images/JapaneseAnimationGuide.pdf>.

Halle, Louis. “A Hopeful Future for Mankind.” Foreign Affairs (1980). Foreign Affairs. Web. 17 Mar. 2015. <http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/33959/louis-j-halle/a-hopeful-future-for-mankind>.

Sumisawa, Katsuyuki. Gundam Wing. Tokyo: Kodansha, 1995. Print.

Sumisawa, Katsuyuki. Gundam Wing: Battlefield of Pacifists. Tokyo: Kodansha, 1996. Print.

Sumisawa, Katsuyuki. Gundam Wing: Episode Zero. Tokyo: Gakushukenkyusha, 1997. Print.

Sumisawa, Katsuyuki. Gundam Wing: Frozen Teardrop. Tokyo: Kadokawa Shoten, 2010. Print.

新機動戦記ガンダムW(ウイング. 7 Apr. 1995. Television.