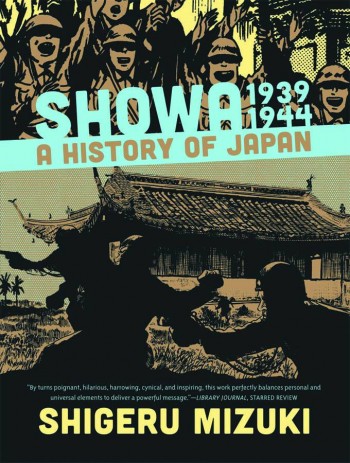

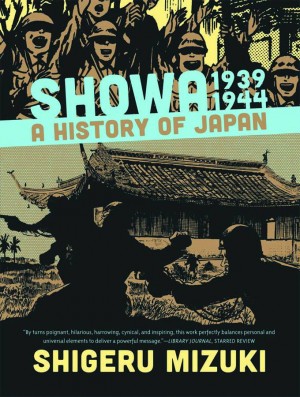

GRAPHIC NOVEL REVIEW: Showa 1939-1944: A History of Japan, Vol. 2

NO EXCUSES: WARTS AND ALL One of the ironies of life is that many of us know a historical event but in actuality, we know nothing at all. Thought provoking, contradictory, you say? Not actually for we are just mere humans whose memories are either fleeting as times pass by and being embellished with hindsight […]

NO EXCUSES: WARTS AND ALL

One of the ironies of life is that many of us know a historical event but in actuality, we know nothing at all. Thought provoking, contradictory, you say? Not actually for we are just mere humans whose memories are either fleeting as times pass by and being embellished with hindsight and reconfiguration of our thoughts to our liking. One historical event in this case is the Second World War. It is the most favorite war topic many want to tackle with, be it in the entertainment, academic, literary and the public sphere. We have that too. As what Conrado de Quiros once said, his generation’s view on the war centered more on the great action hero Fernando Poe Jr.’s over-the-top portrayal as the freedom fighter against the Japanese forces. We have Drs. Ricardo Jose and Augusto De Viana, and Prof. Jose Custodio as two of the finest experts on that period. And, due to the internet, there are plenty of photographs to be seen about the war. How about in comics? Seriously, there are aplenty if one delves. I decide to choose Showa 1939-1944: A History of Japan by Shigeru Mizuki.

This work is massive, clocking about 550 pages and worse; this is the second chapter of Shigeru’s three volume historical epic that stretched from the 1920s up to the 1950s. Showa is the Japanese name of the reign of Hirohito, Japanese emperor for the most part of the 20th century. This massive graphic literature combines the elements of history, autobiography, and Shigeru’s brand of visualization and storytelling that truly justifies why he’s one of the best artists in the history of Japanese comics we ever witness. In true manga fashion, this fine work should be read from right to left, and it is colored in black and white. So, fans of manga and anything about Japanese will surely love this. And the pacing is so well-balanced and never felt so rushed that even just browsing this titan will make the readers appreciate the mastery of the artist’s sequential narration, illustrations, characterizations, and his brand of humor.

This is a very personal work for Shigeru. He tries to recollect and reconstruction what happened in Japan during the tumultuous decades, or more specifically the Showa reign, of the 1920s up to the early 1950s. Of course, this is a Japanese point-of-view about Japanese history, especially the controversies surrounding the eras concerned. But he is neither an apologist nor fully blinded to the horrendous acts of brutalities and propaganda that accompanied those times. He wants to show the reading public and comics fans the human side during those times, not what majority Japanese graphic novels try to justify and defend on Japan’s actions. He actually erased the stereotypical images of Japan, its society and people through the presentations of humanity in the midst of anxiety, uncertainty, hopes, and sacrifices, not sugarcoating the obvious.

Not only he presented himself in the pages but he showed the various social and cultural dynamisms occurred in his hometown and the places he went and stayed during the entire narration. As a student of history, this is a real treat for I can glimpse in Shigeru’s eyes how the Japanese society then viewed and reacted to the developments happened in Japan and the rest of the world. Though for comedic effects, he created witty and deadpan dialogues, but I can say this is also a contemporary piece of evidence for he speaks from his memory as closely and authenticated as possible. Truly, this era (and the war) defines him and the rest of his generation. I am particularly engrossed on the multiple occurrences of “rations” and how the young Shigeru tried to get around with this practice on and off Japan. In this volume, Japan was in the brick of giving in to the demands of crossing the Rubicon, particularly with its dealing with the United States in response of the second Sino-Japanese War in the 1930s. For obvious reasons, Shigeru did some extensive researches regarding the forces behind the wars mentioned, including some famous and powerful personalities. In that matter, he juxtaposed his other imagery to highlight those world events, particularly the United States and the places Japan invaded, conquered and subjugated during the war. And the cultural practices and norms then are spot on for we can concur that not everyone (including Shigeru) agreed upon on those practices, including the constant slapping whenever mistakes he and others committed. And how humorous he illustrated himself whenever his younger self was slapped/smacked/beaten! Speaking of visuals, he demonstrates here why he is one of Japan’s best manga creators. He presents how versatile he is-from the super detailed illustrations of armaments, tanks, and aircraft carriers, battleships; to old-fashioned manga styles that most manga lovers are so familiar with. He utilized various collage techniques by highlighting important historical photographs to give his historical piece a sense of place and time, and proper contextualization as much as possible. I couldn’t even restrain myself smiling and laughing on his meta-narrative illustrations and narration whenever his comic imageries conversed with one another or with actual historical figures. That’s how the breaking the fourth wall narrations work!

Moreover, this book has good end notes that explain concisely some of the famous historical personalities and socio-cultural phrases/terminologies in those times. There are a couple of footnotes that quickly points the readers what page in the end notes to turn in just in case further curiosity has to be satisfied.

What made me buy this volume is that it mentions of the Philippines. Undeniably, Japan targeted the Philippines since the latter was an American possession, and part of Japan’s propaganda “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere”—freeing Asia from colonial/imperial rule rhetoric. Shigeru mentions this slogan as a benign presentation of making Japan as the “liberator”, but in actually, Japan wanted to rule Asia and the rest of the world, if possible. POWER intoxicates, indeed! This is particularly true when Japan overstretched its limits in the summer of 1942 by attempting to invade Australia, India, and the further reaches of the Pacific region until its decisive defeat in Corral Sea that year. The artist truly never sanitizes nor glamorizes the realities of war, and the actual information regarding that matter. Shigeru devoted a chapter on the Philippine campaign in 1941 to 1942, particularly the Battles of Bataan and Corregidor; and some mentions of Philippines during 1944. I commend the artist for that one, though I feel that he erred on interpreting some “facts” about the Philippine experience (he was not part of that one, and relied on secondary sources).

First, even though President Manuel L. Quezon declared Manila as an “open city” (meaning, belligerent forces must not bombard nor destroy the city because there are no military forces already; the invading force should instead enter the city), but there are evidential proofs that some Japanese airplanes bombed the Manila nonetheless, maiming and killing many civilians alike (Shigeru called this as “bloodless conquest”). The infamous Bataan Death March is another thing. Shigeru attributed diseases like malaria and diarrhea as the main culprits why many died along the way, including the tropical heat (it’s summer, obviously). Yet, there are again authenticated accounts that along the way, there were systematic killings and maltreatment occurred, like bayoneting weak/sickly/threatening prisoners-of-war (POWs), having some POWs dug their graves before being killed off, and the terrible cramming of remaining POWs in trains towards the final destination that resulted to further deaths. Truly, General Homma (or Honma) Masaharu got all the blame (and was executed by sore loser Gen. Douglas MacArthur in 1945 in the guise of the military tribunal) but Shigeru could not pinpoint the true mastermind of this infamous episode. And speaking of MacArthur, Shigeru did point out the intense debate between the United States Navy and Army regarding the course of action in the Pacific region in 1944, and MacArthur’s ascent to overall command (the Operation Cartwheel part, or in other books, “island-hopping” stratagem). However, if the master dug deeper then he would probably realize that President Roosevelt sided the flamboyant general due to the latter’s massive public popularity and the affinity to the Philippines, not solely on Douglas’s “I Shall Return” promise (more so, he wanted to “liberate” the American prisoners in various places camps in the Philippines, especially in Manila), and the Nimitz’s plan to prioritize Taiwan (which is strategically closer to Japan than the Philippines). Moreover, there were many atrocities committed by the Japanese troops in the Philippines that could run to several pages or turn into a multi-volume historical literature altogether, including the political collaboration of Philippine leaders with the Japanese military superiors led by Jose P. Laurel, Sr. Jorge Vargas, Claro M. Recto, Emilio Aguinaldo, etc. But understandably, Shigeru’s scope is limited to himself, his nation’s experience, and some selected world zeitgeist then.

Despite the omissions Shigeru presented on the Philippine situation, this volume stands as an excellent piece of both historical piece and graphic illustration. Naturally, I still recommend reading credible history books on World War II, particularly our own experience. What I say this second volume is historical in the sense that Shigeru tries to become impartial in dealing with very difficult (and conflicting) pieces of evidences that pictured very polarizing points-of-view of the said epoch. Naturally, he has his biases on being first and foremost as Japanese and to his proud culture and history; but he never stomps to the level of being too extremist to any ideology involve. Similar to the highly influential works Maus and Persepolis, Shigeru tries his best to present multiple and credible perspectives without tarnishing nor distorting the existing evidences, including himself. That marks a great human—presenting humanity in its best and worst—HONEST. It’s time to remember and appreciate our past.